BLACK WHITE

Art from 1400BCE to 2019

January 30th – April 30th, 2022

Milton Art Bank (MAB) is thrilled to present BLACK WHITE, an exhibition of artworks and objects spanning a wide range of mediums, genres, and historical periods. These works explore the many ways black and white are used in art. Black is the absence of visible light, while white contains all wavelengths of visible light. One draws in and absorbs while the other pushes out and repels. These two colors have been locked in binary opposition throughout history: Evil/Good; Dark/Light; Night/Day; Dirty/Clean. However, this belies the true nature of their relationship, for they are actually sympathetic companions, the one needing the other in order to find its fullest expression. For how can we ever truly know what is light without ever experiencing that which is dark?

There are innumerable ways in which artists have used black and white: formally, conceptually, metaphorically, politically, graphically, structurally. Some of the works on view are simply black, some simply white, while others mix the two colors to create striking ranges of gray. There are also works that are neither strictly black nor white, but rather use muted colors to portray an idea black and white, of opposition and pairing. In order to help the viewer better understand some of the larger ideas and motifs found in the works in BLACK WHITE, MAB has invited noted author and art critic Lance Esplund to peruse the exhibition and write about works he considers exemplary of how black and white can function in an artwork. His texts can be found throughout the gallery by the works they describe, and the viewer is invited to use them as their guide through the exhibition.

BLACK WHITE

VIRTUAL WALK-THROUGH

Barbara Goodstein (1945-2015)

Church, New Haven, 2003

Acrylic plaster, paint, wood on board

Courtesy Barbara Goodstein Foundation

Goodstein, who worked with white plaster on painted plywood (an original medium), merged drawing, sculpture, painting, collage, and relief. Here, she distills a church and landscape into idyllic, linear, elastic elements—shorthand interpretations spontaneous and alive; incisive, immediate, graphic. The sculpture’s stark contrasts are reminiscent of chalk drawings on blackboards, X-Rays, and of shadows blackening brightly lit snow during a full moon. Goodstein’s hand is playful, sophisticated, and economical. She conveys both the skeletal scaffolding (the insides) and the gestural overall (the outsides) of her motif. Working in opacity and translucency, she arrives at essences that blend figure and architecture; crucifixion, altar, icon, and memory.

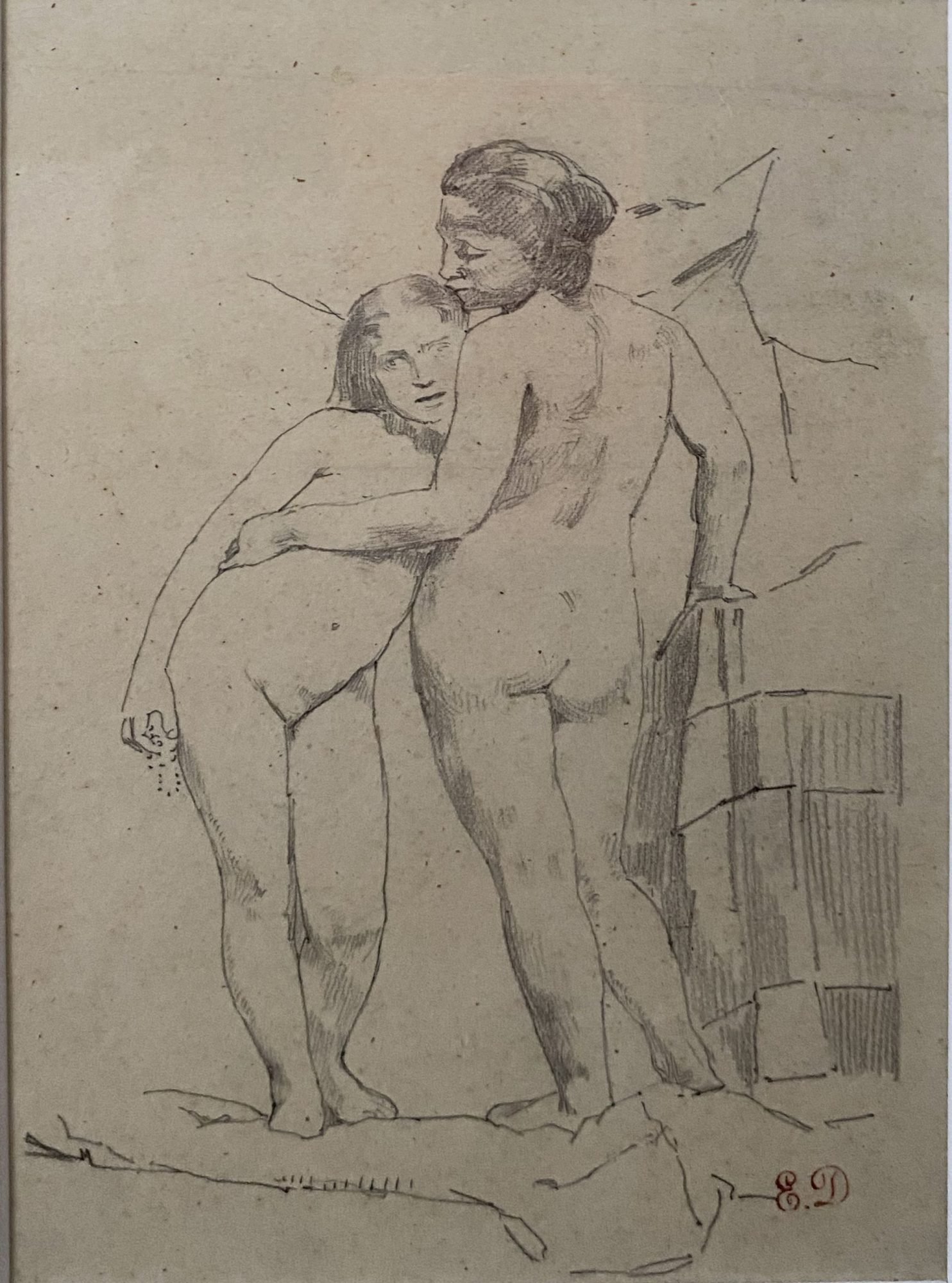

Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863)

Deux nus, d’après photographie, 1850

Pencil on paper

Private Collection

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867)

Study of a Youth (study for the fresco “The Golden Age”), 1849

Pencil on paper

Private Collection

The contemporary 19th-century French painters Delacroix and Ingres have long been polarized: Delacroix is designated as the Romantic Dionysian—a champion of free, loose, expressionistic color; Ingres, seen as the Neoclassical Apollonian draftsman—a champion of precision and line. Here, seen together, their passions feel neck-and-neck. Ingres’s study of nude male figures for his orgiastic fresco, The Golden Age, in which he said he wanted to create something altogether heathen, something “Greek,” loosens up; its trembling edges courting the freely sensual. Ingres’s delicate, crystalline line is heightened, if not further eroticized, by a tantalizing primed surface reminiscent of sparkling marble. Meanwhile, Delacroix, tightening his two nude figures’ weighty volumes between pressed contours, like nestled fruit, slows us down, rocks us into a languorous rhythm.

Alessandro Magnasco (1667-1749)

St. Ambrose Standing in a Niche, circa 1725

Oil on paper, laid down on canvas

Private Collection

The Italian Baroque visionary artist Magnasco was a masterly tonal painter. His palette was dark, even morose: seeping, liquefied zigzagging browns, grays, blacks, and blues—pictures in which uneasy strands of light, unable seemingly to gather purchase, and hounded by darkness, dart and glance across and through forms. Magnasco’s subjects were often claustrophobic landscapes, ruins, crowded interiors, and religious scenes—such as hooded monks and the tortuous Inquisition; and his figures are elongated and undulated, like stretched taffy, cracking whips, melting wax. Yet, as in this grisaille painting, St. Ambrose Standing in a Niche, they remain solid, monumental. Besides his gorgeous, gloomy light, what keeps us moving and engaged are Magnasco’s restlessness, his willful distortions, his equivalence of violence with eroticism and of humans with nature and beasts, and, especially, his inimitable whiplashing line—as if he saw the world made up not of people and things but of lightning bolts, clashing in a thunderclap.

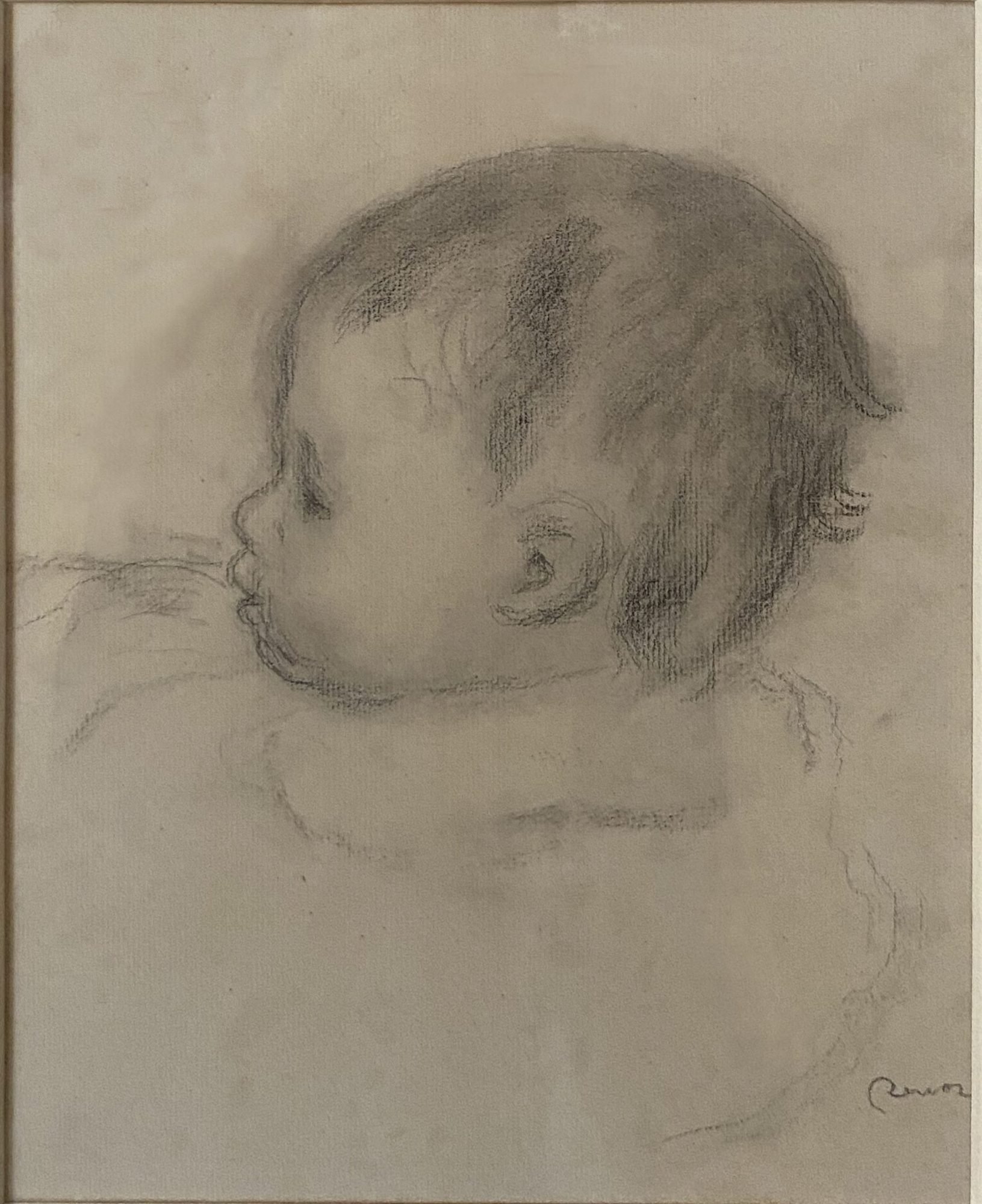

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919)

Portrait of Jean Renoir, circa 1902

Pencil on paper

Private Collection

The subject of this pencil study, for the oil painting Gabrielle and Jean (1895), in Paris’s Musée National de l’Orangerie, is Renoir’s second son, Jean (1894-1979)—the filmmaker who brought us masterpieces such as La Grande Illusion and The Rules of the Game, as well as the biography, Renoir, My Father. Jean was probably drawn here while sitting on the lap of Renoir’s teenage model and Jean’s nursemaid, Gabrielle—fidgeting and playing with toy animals, as he is in the finished painting. Renoir depicts Jean as a plump cherub, a downy cloud; the smudged, double- and triple-contour edges of his head quivering, conveying an infant in constant motion. Jean recalled that his father was not overtly demonstrative, except through his art: “With sharp but tender touches of his brush,” Jean wrote, “he would joyfully caress the dimples in his children’s cheeks or the little creases in their wrists, and shout his love to the universe.”

Hans Leonhard Schäufelein (1480-1540)

The Last Supper, nd (lifetime impression)

Woodblock print, four sheets

Private Collection

In Schäufelein’s depiction of The Last Supper, white light, emanating from Christ’s diamond-shaped halo, ripples outward, as it permeates and begins to dissolve the spaces and shadows of the composition—eliminating depth and darkness. Everything is illuminated, pushing forward, and—as with the architecture’s central support column—nearly flattened against the front plane of the picture, which feels ready to burst. Schäufelein’s light-filled Last Supper table—with Christ at the helm and the apostles as insufficient anchor and ballast—swells, begins to turn and to threaten to roll over us, like a wave about to break on our shore.